St. Mark’s Lions

What connection is there with Saint Mark’s Church in Worsley and lions?

The Winged Lion

The heraldic symbol of ‘Saint Mark’ or ‘Mark the Evangelist’ is a winged lion, which is also the title of the regular magazine for St. Mark’s Church in Worsley.

Saint Mark lived from 12 AD to 68 AD and his feast day is celebrated on 25th April.

The lion is the symbol of St. Mark for two reasons:

He begins his Holy Gospel by describing John the Baptist as a lion roaring in the desert (Mark 1:3).

His famous story with lions, as related to us by Severus Ebn-El-Mokafa: “Once a lion and lioness appeared to John Mark and his father Arostalis while they were traveling in Jordan. The father was very scared and begged his son to escape, while he awaited his fate. John Mark assured his father that Jesus Christ would save them and began to pray. The two beasts fell dead and as a result of this miracle, the father believed in Christ.”

The Worsley Lions.

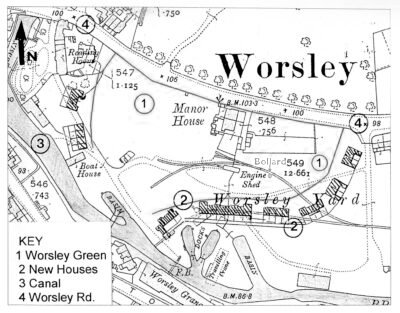

Work on Worsley New Hall started in 1839 and was completed in 1846 as the home of Lord Francis Egerton, later to become the 1st Earl of Ellesmere. Today the grounds are the home of RHS Bridgewater.

At the hall were two bronze lions that, it is believed, stood guard on either side of the north entrance.

In 1945, just prior to the new hall being demolished the 5th Earl of Ellesmere presented the lions, along with the Bridgewater Clock, to St. Mark’s church. The clock was installed in the tower for the centenary of the church in 1946 and the lions were originally stood outside the west door.

A local tale of the time held that when the Bridgewater Clock struck thirteen (which did and still does, at 1am and 1pm) the two lions would change places, but this might be related to the effects of a lunchtime or evening at the village public house, the Bridgewater Hotel.

During the time of Canon Colin Lamont (1947 to 1953) the lions both disappeared but were found a few weeks later in the vicarage garden shrubbery. Later in this period one of the lions disappeared, never to return! After this theft the remaining lion was brought inside and now stands as though guarding the Ellesmere Chapel.

The bronze lion now in the church does not have any wings. However, it is stood on its hind legs (Rampant) and holds a Pheon (Heraldic arrow) with its front paws. The coat of arms of the Egerton family is a lion rampant with three pheons.

There are no markings or inscriptions on the lion to indicate when or where it was made. Although its apparent association to the Egerton coat of arms suggests the pair of lions were specially commissioned.

One thing we do know is that the lion is made of bronze, so it is weighty. How it was carted off to the shrubbery and by how many is for the imagination.

Part of the lion’s tail has been broken off – possibly damaged on its visit to the shrubbery.

Mark Charnley Green Badge Bridgewater Canal Tourist Guide

If you would like Mark to give you a more detailed tour of St Mark’s Church in Worsley and the Bridgewater Canal you can contact him on 07884 121021 or markwcharnley@gmail.com

Images

Lion photos taken by Mark Charnley with kind permission of St. Mark’s Church, Worsley

Cover image of Winged Lion magazine with kind permission of St. Mark’s Church, Worsley

References

Changing Scene by H. T. Milliken – Two hundred years of church and parish life in Worsley.

This book is available for sale at St. Mark’s Church.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Jill Rawson, authorised lay minister of St. Mark’s for her cooperation with this article.